Backstory

The story behind the story. Every book has one.

For me, it began when I was a student. At twenty-one, I managed to spend my last semester of college in the former Soviet Union. This was the late 1970s—the height of the Cold War—and exchange programs were few. Ohio State University had one, and I joined a group of thirty-some American and Canadian students on the adventure of a lifetime.

We lived in a hotel for foreign students near Moscow State University and every day took public transportation to the Pushkin Institute where we studied mostly Russian language. I can still hear the subway system voice warning that the doors were closing. Ostorozhno, dveri zakryvayutsya.

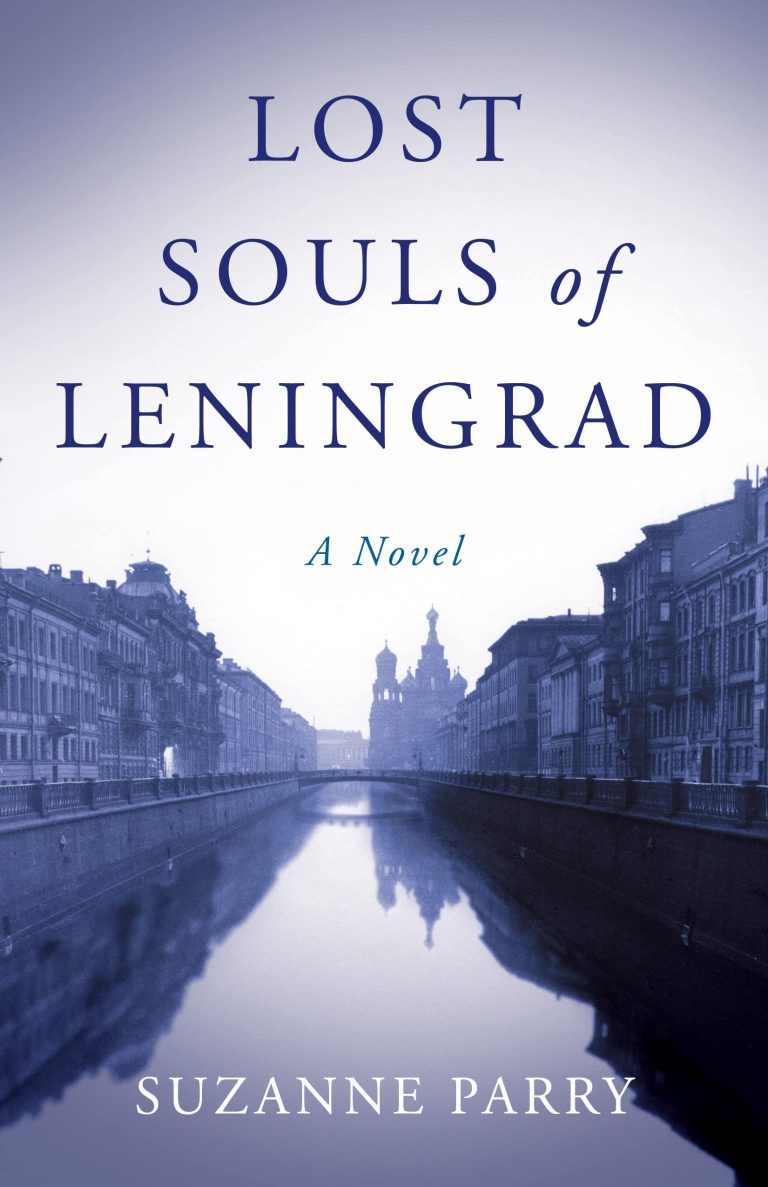

We traveled too. Excursions outside of Moscow, and one longer trip to Leningrad. It was a drab cold March in the city of Lenin, which changed names three times in the 20th century. Before 1914 it was St. Petersburg; from 1914-1924 it was Petrograd; from 1924 until 1991, Leningrad; and since 1991 it is again St. Petersburg.

The water in the canals and rivers of the city ran high. I don’t recall seeing the sun once during our several days there. There was a lot to take in, but of all the museums and monuments, cathedrals and monasteries, theaters and schools, my strongest memory is of the Piskaryovskoye cemetery. The resting place for some half-million unknown casualties of the siege of Leningrad in World War II.

The cemetery is both graceful and stark. A broad entrance looks out on a wide, 500-meter-long alley lined with flower beds toward the centerpiece of the memorial at the far end: a large bronze Soviet-style sculpture of the Motherland, behind which is a granite wall inscribed with the words of poet Olga Berggholts, herself a siege survivor.

Extending from the pathway on both sides are large rectangular mounds, nearly 200 mass graves. On the day I first saw the cemetery, the graves hid under a spring snow, but years later I saw them again in summer, covered with bright emerald grass. Full of life.

At the entrance there is a small museum. The most moving part of which are the diary pages of Leningrad pre-teen Tanya Savicheva, who chronicled the deaths of her entire family with simple sentences and the date. The diary ends with the most forlorn of entries: Tanya is left alone.

The plight of the citizens of Leningrad never left me. Oppressed by Stalin and then cornered by Hitler. Lost Souls of Leningrad is my humble effort to draw attention to those terrible events and the ofttimes ramifications of authoritarian rule.